A Long Way from the Fatherland

Author: Robert Price

Published: Online Only April 2024

The name Ferdinand von Mueller is one that crops up frequently, whether reading on science, Australian geography, history or exploration, but particularly in the context of botany and taxonomy. It seems unnecessary to list the plants whose botanical name finishes with muelleri, muelleriana, ferdinandi or ferdinandiana, as most readers will have come across numerous examples of species (and a genus, Muellerina) honouring the man. He was but one of the many German-born botanists and scientists who came to this country. To name just a few: Hermann Beckler, appointed botanist and doctor on the Burke and Wills expedition of 1860; Maurice Holtze who established Darwin’s Botanic Gardens at Fannie Bay in 1878; explorer and scientist Georg von Neumayer; Richard Schomburgk, curator of Adelaide Botanic Garden from 1865 until his death in 1891; and surely the most famous, natural scientist and ill-fated explorer Ludwig Leichhardt. It has been generalized that they brought with them the “epistemic traditions” of their country of origin. As far as I know, this is a truism meaning nothing more than that they were seeking to gain knowledge of their chosen discipline. This can certainly be said of Mueller, but there was something more that was driving him towards the Australian colonies.

He was born in Rostock on the thirtieth of June, 1825, the only son of Frederick and Louise Mueller, but with an older, and, subsequently, two younger sisters. From an early age, Ferdinand could not help but be aware of his father’s persistent dry cough. This was a time when the ancient disease called phthisis was particularly prevalent. It came to be known as consumption and later, tuberculosis. Not until 1880 did Robert Koch identify the tubercle bacillus and write, in 1882, that “one-seventh of all human beings die of tuberculosis.” It is a condition that can affect many parts of the body. For instance, scrofula, a word from which we derive the plant family name Scrophulariaceae, is tuberculosis of the neck glands, but it was pulmonary tuberculosis, the most common and deadly form, from which only one in a hundred could be saved, that infected Frederick Mueller. After four years of decline, he died in 1835 when Ferdinand was only nine.

The next year, Louise moved the family to Tonning where she had family who could help with raising the children. The disease, however, followed them. She was only 43 when, in 1840, she succumbed. Before she died, the adolescent Ferdinand’s mother had arranged an apprenticeship for him with an apothecary in the nearby town of Husum, and it was here that he began developing the habits that would persist throughout his lifetime. He finally felt released from the ghastly spectre of death that had been present for the last ten years. As plants still played an important part in pharmacy, a requirement of the trade was to assemble an herbarium, and the escape into the natural world this provided was the tonic Ferdinand desperately needed. In addition, the discipline of study created for him an ordered world where the insecurity of his unhappy childhood could be left behind. Where possible, he avoided returning to Tonning, particularly when his older sister Iwanne began showing the early symptoms of TB. In 1843, she too died of the disease.

The 1840s were exciting times in botany. Alexander von Humboldt had completed a journey through Russia, his second great expedition, and was publishing the first two volumes of his masterwork Cosmos. A Sketch of the Physical Description of the Universe. Sir Joseph Banks had died twenty years previously but his influence lived on in the work of his “young men” whom he mentored, such as George Bentham and William Hooker. The latter had just been appointed as the first Director of Kew Gardens in London as Ferdinand Mueller was beginning his apprenticeship in Husum. These were all men already famous for their scientific prowess but it was arguably two lesser-known Germans who had the greatest effect on the young Ferdinand.

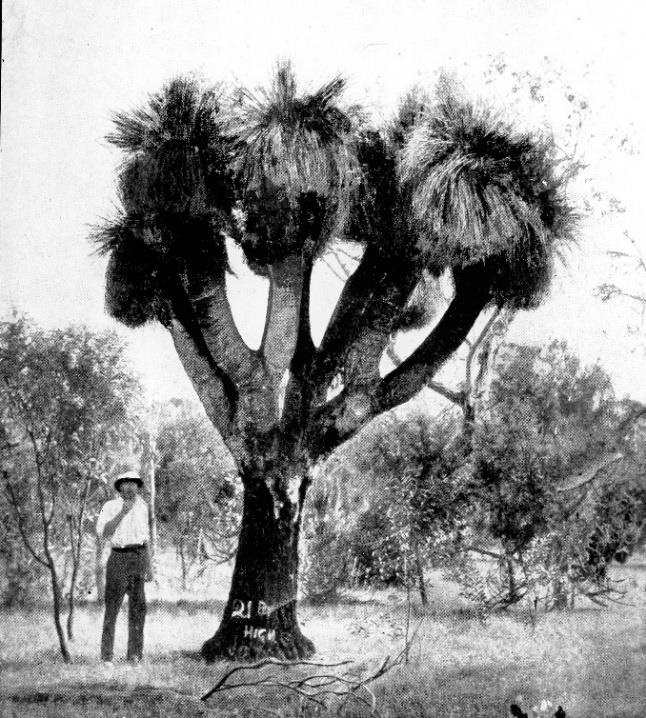

A 21 ft Xanthorrhoea preissii, one of the 100 or so plant species named after Dr. Preiss.

Photo C E Lane-Poole

One of these was the botanist-naturalist Dr Johann Preiss, an old family friend. Word had reached Europe in the 1830s of the uniqueness and diversity of Western Australia’s flora. The director of Hamburg’s Botanic Gardens, Professor Johann Lehmann, raised funds to send Preiss to the colony with instructions to “collect the products of [natural history] and arrange those products in a useful way for the purpose of science”. He arrived in Perth in 1838 and immediately began collecting, travelling widely alone and on foot. There were no laws prohibiting German naturalists collecting in British colonies, and despite (or possibly because of) being the colony’s best qualified botanist, Preiss encountered the opposition of local collectors with connections in London’s botanical establishment. The chief botanist, James Drummond, sent a warning to William Hooker that Preiss was collecting for the Prussian, Russian and various German states. Nevertheless, he continued his work, relying on the assistance of homesteaders and Nyungar people, diligently recording information the latter passed on about specimens. Attempts to sell his collections to the British Government were rejected, though considered by Australian naturalist Rica Ericson to be “far superior to others being offered for sale in England”. In 1842, Dr Preiss returned to Europe with the largest collection then to leave the colony: 200,000 plants covering 2,500 species in addition to species of birds, reptiles, mammals, fungi, algae, lichens and more. His reports of botanizing in Western Australia were completely fascinating to Ferdinand Mueller. The seed was planted. In an unfortunate postscript, 1842’s Great Fire of Hamburg prevented the construction of a natural history museum, and the purchase of Preiss’s collections planned to be housed there. Debts forced him to sell to various herbaria and private collectors, with many specimens simply disappearing. The two volume Plantae Preissianae was compiled by Professor Lehman but when Preiss’s standard reference set used for the publication was offered by Lehmann’s estate for sale to Germany, they declined. It now resides in the Lund Herbarium in Sweden.

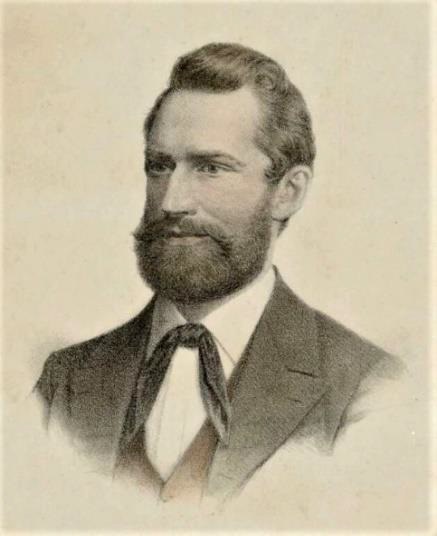

Ludwig Leichhardt

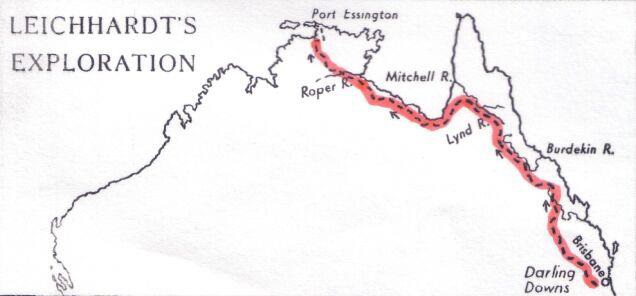

Ludwig Leichhardt’s Exploration

The other German who greatly influenced Mueller, and who went on to become considerably more well-known to Australians than Dr Preiss, was Ludwig Leichhardt (pictured above). He had sailed to Sydney, arriving in 1842 and, being the romantic he was, immediately fell in love with the place. An application for the position of curator at the Sydney Botanical Gardens was ignored by William Hooker but, undeterred and possessing enough funds and sufficient charm to gain the assistance of settlers along the way, Leichhardt travelled alone to Brisbane through parts of the colonies as yet unexplored. When plans by the government for an expedition through Queensland to Port Essington fell through, Leichhardt proposed to organise his own. It set out from the Darling Downs in September, 1844, and no news of the party was heard for 16 months. Leichhardt’s arrival in Sydney by boat from Port Essington in January, 1846, caused a sensation. They had been assumed lost and the news of discoveries of suitable pastoral land and rivers brought Leichhardt instant fame.

Meanwhile, Mueller, by the time he had turned 21, had received a degree in pharmacy and a Doctorate of Philosophy. He was offered a partnership in the apothecary in Husum but an episode of poor health and the early signs of tuberculosis in his sister Bertha caused him to reject the prospect of a safe and prosperous life in Germany. Dr Preiss’s accounts of an agreeable climate (and the plants) in Australia decided Mueller. He would travel to the colony of South Australia where there were already two thriving Prussian settlements and take both sisters, Bertha and Clara, with him. After a five-and-a-half-month voyage from London, they disembarked at Adelaide in December, 1847.

Early fortune favoured them. In a matter of days, the Muellers were offered accommodation with a local family, the Davenports, and Ferdinand had secured a job in a pharmacy owned by a pair of fellow Germans. In his spare time, he walked all over Adelaide and the Mount Lofty Ranges, collecting botanical specimens. But not all went smoothly. He was swindled out of a large sum of money, and then, when he lost more on a failed farming venture in the Bugle Ranges, was forced to return to his old job at the Adelaide chemist.

Eight months after the completion of his successful exploration of western Queensland, Ludwig Leichhardt set out again from the Darling Downs, intending to cross the north of the continent from east to west. He was, however, forced to abandon the attempt after five months. He immediately began to organise a similar expedition and left in April, 1848, just months after the Muellers arrived in Adelaide. The journey was expected to take up to three years. This was the ill-fated expedition that was never heard of again.

Mueller was now roaming widely from Adelaide – into the Flinders Ranges alone and on foot, and eastwards to the Murray River where he “found the variety of flowering eucalypts…. utterly absorbing and rewarding”. His early publications such as Notes on South Australian Botany and the (now) quaintly titled Flora of South Australia displayed in its fundamental features were of high quality and being read and noted, not only locally but also back in Europe.

Leichhardt’s disappearance must have made quite an impression on Mueller. By 1851, he was concerned enough to begin writing publicly to newspapers with estimates of Leichhardt’s position and proposals to send out search parties. This did not happen and Mueller was furious with government inaction. He continued writing and speaking about Leichhardt, incredibly, for over forty years, calling for expeditions to ascertain what had happened to the explorer, but it seems like the country had forgotten Leichhardt. After the premature loss of family members, Mueller must have felt haunted by death. Two of the Victorian era’s many obsessions were death and collecting. Hypochondria was rife and parlours were stuffed to overflowing with collectables. The natural world was represented by animal heads on walls and skins on floors, elephant’s foot umbrella stands, pinned beetles, butterflies and moths in glass-fronted cases along with fish and birds and dried flower and foliage displays. Fitting neatly into this template were Mueller’s predilections: paranoia about his own health fed by the trauma he had experienced as a young boy and man, and the collection and ordering of botanical specimens.

The 1851 discovery of gold in the Colony of Victoria lured fortune seekers to Melbourne from all parts. Bertha’s health had improved and both sisters were engaged to be married so Mueller felt confident enough to leave his job and take a gamble on moving to Melbourne in the pursuit of money and a career in botany. He was introduced to the Governor, C J La Trobe, somewhat of a polymath with an interest in botany, who was looking for someone to fill the newly created position of Government Botanist. Ferdinand Mueller was in luck. A recommendation was sent to Sir William Hooker at Kew Gardens and he approved the appointment.

Only a matter of days later, Mueller left Melbourne on horseback in the company of John Dallachy, the curator of the Botanic Gardens. They were heading north east for the Victorian Alps on the original Sydney to Melbourne route pioneered by Hume and Hovell. A mountain the explorers had passed thirty years previously apparently reminded them of a reclining buffalo and so they named it Mount Buffalo. This was where Mueller and Dallachy were aiming for. They passed through the Ovens River valley and beyond it, the Beechworth Plateau where 10,000 diggers worked the goldfields in a frenzy of activity. By the time gold ran out, the landscape had been devastated. The pair climbed the slopes and gullies through stands of manna gums, peppermint gums and candlebark (Eucalyptus rubida) with wattle, bottlebrushes, fringe myrtle and daisies beneath, till reaching the 5,600 feet high Mt. Buffalo plateau’s snow gums, alpine grass, heath and bog. Here they camped for a week and set about collecting, Acacia dallachiana and Kunzea muelleri just two of the many species named.

Dallachy had limited leave available, so returned to Melbourne, but Mueller carried on, climbing Mt. Buller. At almost 6,000 feet high, it was truly alpine with herb fields and no trees covering the upper slopes. After two months travelling and having covered 1,500 miles, he arrived back in Melbourne with nearly a thousand plant specimens. Mueller’s report of the expedition revealed his love of exploration and his new job, and, after five years in his new homeland, his prospects looked good.

Over the next three years, Ferdinand Mueller was to undertake two more exploratory journeys in Victoria and southern New South Wales. The first was through 2,500 miles of territory such as the Grampians, along the Murray River from Swan Hill to Albury, through the Bogong Mountains to Omeo, and, via the Buchan, Tambo and Snowy Rivers, back to Melbourne. He was away for six months and returned with 496 specimens, 120 of which were new species. On the second journey, he climbed the 7,314 ft. Mt. Kosciusko where he fell ill with a fever. After a fortnight, where his fear of contracting TB was revived, he recovered. The new country’s climate had greatly improved his disposition, travelling had toughened him up and he could not quite credit how much better his health was.

In the six-month period between these two expeditions, Mueller joined the Melbourne German Club, and here the food, language and company allowed him to be himself.

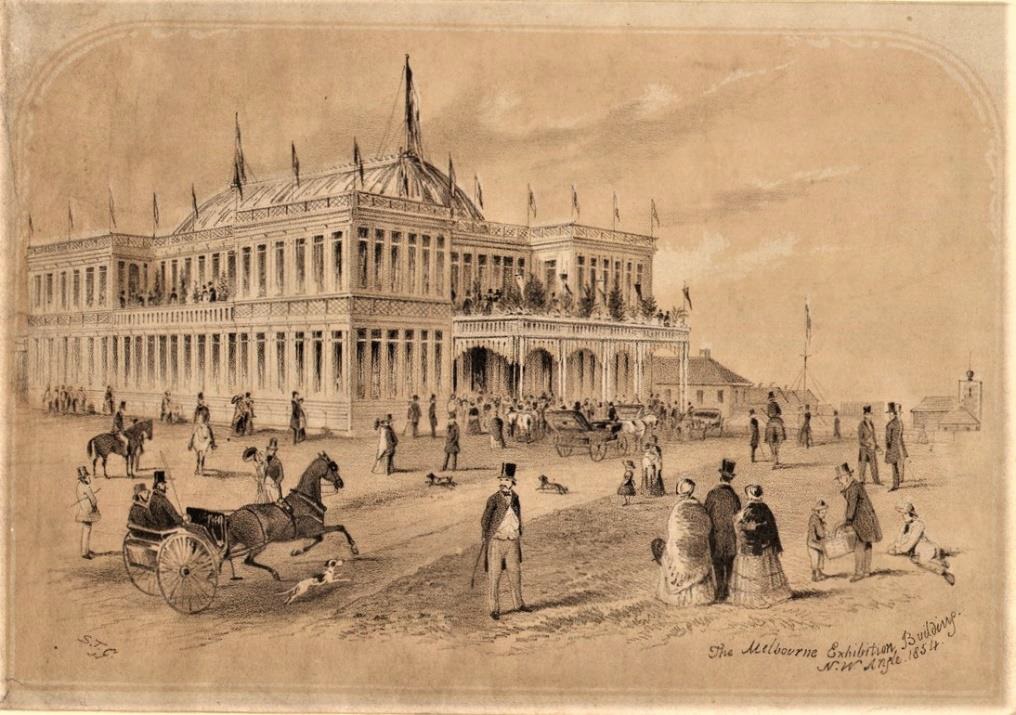

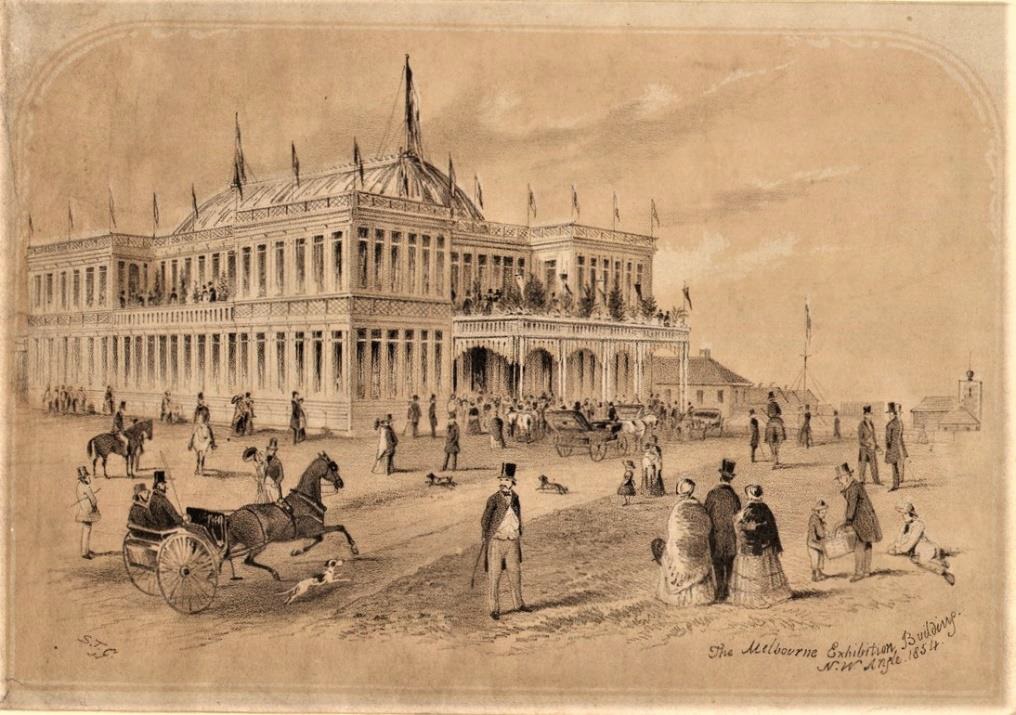

The Great Exhibition in Hyde Park London in 1851 inspired copies all over the world. Not to be left out, Melbourne set to work constructing its own mini-Crystal Palace in William Street and, only two weeks before Mueller left on his third expedition, the Melbourne Exhibition opened. His growing renown had seen him made a member of the organizing committee, given the title of Commissioner, and, as noted by a reporter from the Argus daily newspaper: “the botanical researches of Dr. Ferdinand Mueller secure effect from the magnificent specimens of colonial forest wood, ferns, lichens, grasses &c., which that gentleman exhibits.”

In the 1855 edition of the Victoria Nautical & Commercial Almanac there appeared an article by Dr. Ferdinand Mueller on the “Exploration of Australia”. It called for an expedition to northern Australia, ostensibly for exploratory and scientific purposes, but later in the article, it became obvious that the fate of Ludwig Leichhardt was still firmly on Mueller’s mind: “humanity for Leichhardt and his followers would make it imperative that (the expedition) should be speedily undertaken……who will dare say it is impossible that some of them are alive amongst the natives”.

Correspondence on botanical matters between Mueller and Sir William Hooker in England was undoubtedly helpful to Mueller’s cause. He also made sure that Hooker received a copy of his article on Australian exploration. Subsequently, news arrived in Melbourne that the Duke of Newcastle, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, was to finance an expedition to north west Australia. It had been approved by the Royal Geographic Society and was to be led by Augustus C. Gregory with his brother H. C. Gregory as second-in-command and Hooker’s friend Thomas Thomson as botanist. When Thomson was unable to go, Hooker instead recommended Mueller who immediately applied for 18 months leave without pay. Writing to Hooker, Mueller played up the dangers involved in the expedition and the sacrifices he was prepared to make in participating. All specimens collected on the journey were to be sent to England but Mueller wanted to keep a collection for himself for the purposes of writing the as yet unwritten Flora of Australia. Permission was granted by the Chief Secretary of the Colonies. No mention was made by Mueller of Leichhardt.

On July 18th, 1855, the expedition left from Sydney aboard two vessels, the Monarch and the Tom Tough, bound for Moreton Bay. On arrival, they crossed the bar of the Brisbane River and took on supplies which included 200 sheep and 50 horses. From here, they sailed north. Passing Queensland’s highest peaks, Mount Bartle Frere and Mount Bellenden Ker, Mueller speculated on the likelihood of finding Rhododendron ssp. there. He was subsequently proven correct. They rounded Cape York, crossed the mouth of the Gulf of Carpentaria, rounded Melville Island and, finally, reached the Victoria River estuary. On the way, the Monarch had been grounded on a reef for eight days, and other difficulties getting up-river and to shore caused the loss of many horses and most of the sheep. In addition, salt water had got into the hold of the Tom Tough and destroyed some of the rations. Eventually, though, on November 24th, an advance party, including Mueller, was able to leave their camp and head inland following the Victoria River. Once they had reached a point at which the river divided and where the country had improved, they turned back. By December 13th, they were back at the camp, where, by this stage, the Tom Tough had been partly repaired. Meanwhile, the Monarch had set sail, bound for Singapore.

Boab tree (Adansonia gregorii) at base camp on Victoria R. with July 2nd, 1856 carved into it.

Reise-Line

After several more mishaps, on January 3rd, 1856, an exploration party of nine, including both the Gregorys and Mueller, set off again intending to find the source of the Victoria River. Reaching the junction again, they first explored the west branch of the river, then crossed rough terrain to set up a depot camp back on the river’s east branch. From here, a small party of four, again including Mueller, pushed south and on February 9th, reached the source of the Victoria River. They were now in red desert country and A. C. Gregory made the decision to head further south. By March 6th, when a creek bed they were following petered out into a salt lake, they had reached their furthest point south.

On May 9th, the whole party was safely back at base camp having travelled further into this part of the central Australian desert than anyone before. Mueller was happy with the opportunities given him to botanise and Gregory was satisfied that Mueller was fit and strong enough to be an asset to the expedition. He named the highest point of a sandstone range of hills seen on March 2nd, Mount Mueller.

Eucalyptus microtheca in Taroom, Qld., known as the Leichhardt Tree due to the blaze carved into it during the 1844 expedition to Port Essington.

The next stage of the expedition was to be the journey eastwards, then overland through Queensland to Moreton Bay. Mueller had already sent a consignment of plant specimens to the Secretary of the Colonies with the departing Monarch, which was forwarded on to Hooker. It was planned that the Tom Tough would sail to Timor, take on supplies and meet the expedition party at the Albert River on the Gulf of Carpentaria. On board the boat was a letter that Mueller had written to Hooker expressing his disappointment with the number of plant species collected up to that point, a mere 800! These included 12 new genera and 25 new species. A notable one of these was the Coolibah, Eucalyptus microtheca, collected on the Victoria River by Mueller in December, 1855 and first formally described by him in 1859. He also accepted an invitation he had received from Hooker to make a trip to England and Kew Gardens so that he could compare his plant collection to those from India and early Australian collections made by Robert Brown and Alan Cunningham. Hooker had made it plain that this was vitally necessary if Mueller wished to write the Flora Australiensis.

On June 21st, 1856, the overland party set off, heading east along the Victoria River, then cross-country towards the Queensland border. On July 7th, they came across the remains of a camp: trees cut by axe and the ashes of a large fire, but with no obvious signs of violence, they concluded that the party had passed on without incident. A. C. Gregory had seen several of Leichhardt’s camps from previous expeditions in Queensland and the layout of this camp was similar. It could not, however, have been from the 1844 expedition as it had passed 100 miles to the south west en route to Port Essington. Mueller was no doubt intrigued.

Upon reaching the Roper River, water was more easily found, and Mueller collected many edible plants: native spinach and watercress, yams, lotus, and fruits such as melon, figs, rose-apple, mulberries and nonda (below). The latter is the fruit of the small tree Parinari nonda, said to have a mealy, astringent flavour but it is unlikely the explorers would have been able to use the aboriginal method of ripening, i.e., burial for some time in sand.

Early in September, when the party arrived at the Albert River where they had arranged to meet the Tom Tough, the ship was nowhere in sight. After carving a tree with instructions and burying a note describing their likely forward route, they set off the next day down river. Gregory believed they had enough supplies to reach Moreton Bay. Numerous rivers flowing towards the Gulf of Carpentaria, such as the Gregory, Leichhardt and Flinders, were crossed before reaching the Gilbert which they followed up river in a south-easterly direction. The Great Dividing Range was traversed and on October 16th, the Burdekin River reached. On their way south, at least two more of Leichhardt’s old camps were encountered but, of course, no news of the explorer or his party was heard. The Gregory expedition arrived in Brisbane on December 16th, 1856, a resounding success. Not one man on the expedition had been lost, and, though attacked twice by Aborigines, none were killed. Mueller had collected 1500 plant specimens but was most likely disappointed that no trace of Leichhardt had been found. Before travelling to Sydney, he spent a short time botanizing in the Glasshouse Mountains north of Brisbane but I have been unable to find any records of what he collected locally.

In Sydney, Mueller spent several months working on specimens collected on the cross-country return journey. The greater part of his collection had left from the Victoria River on board the Tom Tough bound for Timor. It was transferred to another schooner, the Messenger, which had left Java in September to meet the expedition at the Albert River. However, no sightings of the vessel were recorded before she reached England, by which time the whole of Mueller’s collection of plant specimens had been destroyed by damp. Severe disappointment was expressed by both Mueller and Sir William Hooker, with the latter still being adamant that Mueller must come to England. Sir William decided to entrust his son, Dr Joseph Hooker, with the task of convincing Mueller, but despite correspondence indicating his intention to comply, Mueller never goes. He remains in Australia for the rest of his life.

On his return to Melbourne from Sydney, Mueller was offered, and accepted, the position of Director of the Botanical Gardens. He began work with the aim of improving the gardens for the public: many native plants were established, labelling was undertaken, a new conservatory was planned, and gravel paths were made to better access the plantings. It seems, though, that Mueller came under the dubious influence of Professor Fredrick McCoy of the University of Melbourne, who was to go on to become an enthusiastic promoter of the Acclimatisation Society of Victoria. He is described by Edward Kynaston as a “sentimental ass” and McCoy’s own words confirm it: “There can be no doubt that those delightful reminders of our English home…..thrushes, larks, blackbirds, starlings and canaries…..will now have spread…..over a great part of the colony (so that its) present savage silence (will be) enlivened by those varied, touching, joyous strains of heaven-taught melody”. Even though there were plenty of native birds making use of the botanical gardens, Mueller was encouraging the introduction of “foreign birds”. The baleful ideals of the Acclimatisation Society were so mindlessly accepted by the Victorian establishment that a proposal to introduce monkeys to the colony was endorsed by the Governor of Victoria, Sir Henry Barkly. Fortunately, that hair-brained scheme did not eventuate, but, still, farmers’ reports of the damage to their crops caused by introduced birds did nothing to deter the members. Mueller was amongst them.

His involvement with the society, however, was peripheral. There is only one plant species which became a significant pest for whose introduction he was directly responsible, and that is the blackberry (Rubus plicatus). He sent seed to many parts of Australia, and wherever it took hold, it formed thickets that were ideal habitat for rabbits, one of the few introductions, by the way, for which the acclimatisers were not responsible.

It is apparent that Mueller’s first love was botany, and the second was exploration. It is unfortunate that, on his return to Melbourne, he was also appointed Director of the Zoological Gardens, for he seems to have been out of his depth. With the backing of McCoy, he was all in favour of distributing exotic animals around natural areas in Victoria, particularly to his much-loved high country to where he wanted to dispatch alpacas, llamas and deer. The South American animals proved unsuitable, but the four species of deer now causing significant problems in Victoria are thought to now number one million, half of Australia’s total population.

Nevertheless, Mueller did not lose sight of his first love, and his botanical work continued. He was writing the Flora of Victoria, still with the hope, despite being unwilling to make the trip to England, of being invited to write the Flora of Australia. At his instigation, a long avenue of trees leading to the gardens was planted. In an era of favouring European trees for their reminders of “home”, his choice of species, Eucalyptus globulus, is to be applauded.

Eucalyptus globulus Melbourne Botanic Gardens

The new decade began with two occurrences that were to have a marked effect on Mueller. The first was his inclusion on the committee advising the Victorian Exploration Expedition, better known these days as the Burke and Wills expedition. His first recommendation to be leader, A. C. Gregory, turned it down. Being the pragmatic and experienced explorer that he was, Gregory probably got a whiff of the debacle that was to come. He suggested another experienced explorer, Major Warburton, but the committee, in true parochial fashion, declared that the leader of the expedition must be a Victorian. When the name of an ex-police officer and magistrate, Robert O’Hara Burke, was put forward, Mueller did not object. In light of the outcome, he no doubt wished he had. The failure of the VEE due to a combination of disorganisation, inexperience and bad luck that resulted in the seven deaths of participants, including, of course, Burke and Wills, was a shock to Mueller. As the only member of the committee with experience of outback exploration, he was horrified most of all by the imperative of haste that had been engendered due to the desire to win the race from south to north across the continent.

Operating out of Adelaide, John McDouall Stuart had already made four unsuccessful attempts to reach Australia’s northern coastline. The Victorians were determined to thwart the South Australian’s ambitions, but, as it turned out, Stuart’s sixth expedition was the first one to make the crossing and safely return, losing not one man and claiming what is now the Northern Territory for South Australia. A Commission of Enquiry into the deaths of Burke, Wills et al ran from November 18th to December 30th, 1861, and, much to Mueller’s relief, exonerated the VEE committee of all blame.

The second occurrence was the publication in 1860 by Charles Darwin of Origin of Species. It contained theories of evolution that turned the world of natural sciences upside-down (and round-about). Nature, in the Victorian era, had been considered to be ordered, fixed, and definitely not evolving. In that same year, Sir William Hooker wrote “Many species were simultaneously called into existence on the third day of creation”, and Mueller, being a devout Lutheran, had no reason to question this belief. Indeed, it provided him some security in an uncertain world that plant species could be identified, classified and catalogued, there to remain in their designated place. But by 1862, many botanists were coming to accept Darwin’s ideas, and when George Bentham wrote to Mueller about reconsidering the notion of species being permanent, Mueller was aghast. What he was reconsidering was the “high veneration” he felt towards Darwin, and, in fact, broke off all contact with the man, becoming an ardent anti-Darwinist. Alfred Russell Wallace and Charles Darwin had, between them, “split asunder the dogmas of Christianity” and Ferdinand Mueller was one of those who was finding himself at odds with the scientific times.

And it was not only Darwinism that Mueller was at odds with. In his 1862 annual report on the Botanic Gardens, he concedes that the prestige associated with writing the Flora of Australia will be George Bentham’s, not his. Hooker and Bentham still needed his cooperation, expertise and, critically, access to his plant specimens, a collection of 350,000. They flattered him from abroad in true flowery Victorian style and promised that his name would appear on the title page following the phrase “with the assistance of notes and descriptions communicated by”, and, of course, after that of George Bentham.

Mueller was also under considerable pressure at home in Melbourne. Throughout the decade, he encountered more and more obstruction from the government. Accusations of incompetency were made, legitimate expenses at the gardens were questioned and complaints about seemingly trivial matters appeared in the newspapers. There was a decided air of tall-poppyism and anti-German feeling about it. This all took a toll on Mueller’s health, mental more than anything else, although this was not admitted to by the man himself. Instead, he spoke of the “weak chest” of which he did not suffer, that he was physically ill and “prostrated on the sickbed”, and of “my advancing years”. He was only forty-four years old and what he was suffering from was surely nervous exhaustion. Nonetheless, Mueller undertook a determined defense of his beloved position as Director of the Botanical Gardens by the only means of which he knew: prodigious quantities of letter writing in a sesquipedalian style that was bound to irritate his detractors.

We need to remember that English was not Mueller’s first language. His writing manner, like his speeches, has been described as turgid and soporific. He went to great trouble and into greater detail explaining the workings of the gardens and how and where every penny was spent, but to no avail. In December, 1870, a Board of Enquiry was established with the aim, a foregone conclusion it seems, of making “the Botanical Gardens more attractive as a place of public resort for recreation and enjoyment (by putting in) place a practical gardener in charge of the gardens”. Of the three members appointed to the board, one was from a horticultural firm, one was a nurseryman, and none had any scientific training. In a lecture on The Use of Botanic Gardens, Mueller typically took a long time to say not much: “The objects of a botanic garden must necessarily be multifarious, nor need they be, in all instances, precisely the same”, and on and on it went. Although obscured by “wooly clouds of rhetoric”, what he was saying was that botanical gardens should be scientific, educational, useful and where possible, decorative. Hardly controversial, but the mood of the government, crass and provincial as they were, was that the Melbourne Botanic Gardens that Mueller, as Director, had built up to world fame, would become a public park, just like the others the city already had: colonial egalitarianism writ large.

Incredibly, Mueller had to put up with a whole year of bureaucratic waffling until, in December, 1871, the Board of Enquiry presented its report. It said that the gardens had not been managed “so as to give general satisfaction” and that Mueller’s views were “entirely different from those of the public”. Then as it is now, there was no answer to this nonsense document that could divert the powers that be from their decision: that the position of Director would be abolished, a curator would be appointed to run the gardens, and Ferdinand Mueller would retain his position as Government Botanist.

Ferdinand Mueller

Nick Number

He retreated into his work, the sense of grievance that he felt at his treatment only ameliorated by the more and more awards, honours and titles he received. They began with an honorary degree of medicine from the University of Rostock in 1857, and continued throughout his whole working life until he had accumulated some 160 of them, being one of the most decorated scientists of his age and titled Baron Sir Ferdinand von Mueller, KCMG. These decorations assured him of his place in the world and, once he had received his knighthood from Queen Victoria in 1879, the colonial establishment were obliged to pay him at least some respect. It is unfortunate, but inevitable, that the man is remembered as an eccentric Teutonic hypochondriac. His early family life had him forever worried at the “prospect of an early death”, and he was so consumed by work that, in later life, if a caller arrived at his small South Yarra house, he would give them a seat, promptly forget them, only to rediscover them an hour later! The few photographs of him that exist invariably depict him in a formal setting, adorned with his honours.

Becoming, if anything, more eccentric as he aged, he aged far beyond his years. At seventy, though he had turned into a shuffling old figure of fun, the Baron was still working, still writing, still lecturing. Fifteen years after the 1879 publication of Bentham’s Flora Australiensis, a supplementary volume to be written by Mueller had not been completed. The Queensland Government Botanist, F. M. Bailey, publicly denounced Mueller’s tardy efforts and claimed that “I am probably the most suitable one…..to undertake the work”. For once, Mueller failed to defend his position. It was left to others to put Bailey back into place, which they did. Mysteriously, all of Mueller’s material for the supplement disappeared after his death, so was never published.

Nonetheless, his record stands in the copious quantities of material that was published. He gave much of his life to Australian botany, but, to this day, his legacy is compromised by a reputation for being a difficult old German, undoubtedly deserved, and his many positive qualities remain somewhat overlooked. He was the writer of a nine volume Atlas of Eucalypts and was aware earlier than most of the beauty of the Australian bush and the prospect “of rapidly increasing settlements in those healthy and extensively fertile regions now occupied by forests. Area after area will be cleared for farming operations wherever accessible to traffic, and finally only the steepest ranges will be left to provide timber, if indeed it is not swept away untimely by fire at any moment in a clime where the danger in this respect is greater than in almost any other portion of the globe.” A typically prolix Mueller statement, but prophetic nevertheless. Much valuable work on economically and medically useful plants was done by Mueller, the latter in particular recognized by Australia’s pharmacists. His contribution to the Melbourne Botanic Gardens was considerable: multitudes of plants collected and planted, an herbarium created, and an excellent library established.

He was generous, to the point of naivety. A story goes that when the mother of a boy who delivered Mueller’s paper informed him of her son’s sudden death, he handed over five pounds to help with funeral costs. The next morning, the boy delivered the paper as usual; the Baron had probably forgotten already. And, in an era of educational bias well in favour of men, and with no serious career path available for women in natural science, Mueller at least encouraged women to become botanical collectors for him, amongst them Ellis Rowan. Not one Australian plant was named by a woman in the 19th C, but species named by Mueller to honour women collectors include Atkinsonia ligustrina (Louisa Atkinson), Hakea brookeana and Scaevola brookeana (Sarah Brooks) and Helipterum charsleyae (Fanny Charlsey).

Atkinsonia ligustrina

Johnstone/Shannessy

The death of Ferdinand von Mueller on October 10th, 1896, was commemorated by a funeral that he would have felt only appropriate for someone of his standing in the sciences. The cortege was led by the German Association Band solemnly playing “The Dead March”, a horse drawn black hearse followed, and behind marched numerous dignitaries representing the institutions that had pestered him with their mediocracy: government, the university, the Botanic Gardens, etc. Over his grave towers a granite monument, one of the largest in St. Kilda cemetery. Someone was trying to assuage their guilt over his shabby treatment. No member of his family was present at the funeral.

Ref: A Man on Edge (1981) by Edward Kynaston

Johann Preiss: The Forgotten Botanist (2020) by Anna Haebich

A Taste for Botanic Science (2014) by Sara Maroske