Pruning for Design

Author: Lawrie Smith AM, Landscape Architect

Published: Garden Design Study Group Newsletter, August 2021

For many of us our gardens aspire to be dominantly natural in character, where plants are encouraged to grow ‘naturally’ with minimal human assistance or training. While others take those extra steps to ‘interpret’ nature a little more formally, by a variety of horticultural practices. Pruning is one of those procedures that can ‘give nature a hand’ through careful modification of plants to increase their aesthetic value by accentuating their best design qualities in form, size and flowering.

Pruning seems such a regular process that we all do as part of the garden maintenance and respond to safety issues, but do we ever consider it as a design tool? If you think back through images of the many gardens you have visited in Australia or possibly elsewhere in the world, one aspect will most likely stand out regularly, and that is the way sensitive pruning can greatly enhance the character of a garden. There are so many ways to prune a plant and even more reasons why you should or should not attack a plant with shears or a pruning saw.

You could emulate some of the extreme sculptural hedge gardens like Levens Hall in the UK where it seems that chess pieces have come to life and run riot through a garden.

Perhaps you think of the endless formal hedges that define and divide the gardens of a European chateau into rooms by walls of regularly clipped foliage.

In Japan Azalea are clipped meticulously into undulating mounds of deep green foliage at just the right time to encourage thousands of flowers to pattern the stylised forms.

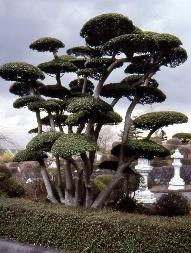

Maybe it is the unique ‘cloud like’ form of clipped trees in Thailand silhouetted against the sky, with many branches like arms supporting balloons of dense clipped leaves.

Some trees laid out in regular grids in the city squares of Europe are regularly pleached to create a very stylised upper level of interlocking hedges to define spaces.

Then there is the pollarding of Australian Eucalyptus in Greece whose upper branches are removed regularly to encourage temporary new canopy growth and to add insult to injury the lower trunks are often whitewashed.

These are but a few of the many ways that humans modify the natural forms and habits of trees and shrubs for design reasons.

From this a question arises – do Australian plants lend themselves to such modification, and is it ‘good design’ to do this? I guess it is possible make a case for some of these less radical procedures. However as the premise “design with nature” is generally applied in my landscape projects, it is hard for me personally to justify or be satisfied by any unnaturally modified plant management.

Of course there are situations, more particularly in urban inner city areas where a unique stylistic approach can be invaluable and logical.

In a past issue of the GDSG Newsletter this ‘Epiphyte Forest’ was described as a vegetated forest of green poles, a design inspired by nature. It was considered to be a logical and realistic way to suggest a Queensland rainforest using our ferns, epiphytes, orchids and climbers to create a strong characteristic environment that is obviously completely ‘unnatural’ but never the less appropriate for its significant position and function in the landscape of World Expo 88.

Up-pruning a form of pleaching, is another method I find very useful, that in design terms is logical and realistic. This hedge of Callistemon ‘Little John’ began life twenty years ago pruned as a low hedge, and over the years it has slowly grown upwards.

It was never intended to assume the form it has now, but as it aged the network of trunks and branches were exposed and the ‘transparent’ qualities of the hedge began to emerge. Now the lower branchlets are purposely removed, leaving a canopy of foliage about one metre above the soil level. Although it still visually divides two sections of the Garden of Native Cultivars, the glimpses through the branches entices the observer to walk around to the opposite side to view that section of the garden. A very valuable way to conceal and reveal areas of the garden that would otherwise be hidden behind a dense formal hedge.

A similar contrived example inspired by a natural feature, was the central garden of a new parkland along the Brisbane River which had originally been a wharf area and coral processing plant.

Coral was extracted from the dead reefs of Moreton Bay and transported by barge upstream to be ground to fine powder, fired and converted to cement. The central garden was designed to simulate the sculptural forms of a coral reef by pruning a hedge of Syzygium ‘Tiny Trev’. Granted this is an intricate regular maintenance process to shape and form the curvilinear hedge – one could ask is this really appropriate design?

So I plead guilty to using ‘manicured’ hedge forms as design elements! But these are rare occurrences for me as a landscape architect. However each of these have fulfilled a special design function which may not have been possible otherwise. Each in their own way, have influenced public perceptions and appreciation of landscape design as well as the innovative use of native species to achieve interesting unexpected design results.

Pruning is advantageous for so many practical horticultural reasons to ensure that a considered garden design is established and continues to be realised. For example most new garden shrub specimens I purchase are first ‘decapitated’ by about one third before planting to encourage a dense branching habit with dense foliage.

Specimen trees are immediately and regularly ‘up-pruned’ to encourage development of a strong trunk and higher level canopy which admits sun under.

Many shrubs in the centre of a garden are similarly ‘up-pruned’ to open up garden space under to be established with small shrubs and covers for added interest. (Image: Deb McMillan)

Tip pruning regularly will encourage density of foliage and promote more flowers as well as enhancing the visual relationship between specimens in massed shrubberies.

Where space is limited espalier comes to the fore, to form small trees flat and narrow against a wall by training and pruning all side branches to effectively create a green wall of foliage.

I’m sure all GDSG members have done most if not all of these varied pruning procedures and could also add many more personal experiences. In conclusion it is fair to say that pruning to form is an invaluable horticultural and gardening activity that with thought and imagination, informs and ensures good garden design. As for me, I justify these practices by saying that the sensitive pruning is inspired by the gentle grazing of a kangaroo or where more radical, as done by storm and bushfire.